Raoul Peck’s Young Karl Marx has succeeded in presenting a holistic view of the young Marx and his time that also speaks movingly to the problems of our time . . . Three aspects stand out as unique: I. Marx’s concept of organization; II. Marx’s challenge to the French Anarchist thinker, Pierre Proudhon; III. The role of women.

Reviewed by Frieda Afary

March 23, 2018

Source: https://www.allianceofmesocialists.org/review-of-raoul-pecks-young-karl-marx-a-must-see-film/

It is not easy to make a movie about a multidimensional and historical figure like Marx without privileging one aspect of that figure’s life over another. Raoul Peck’s Young Karl Marx however, has succeeded in presenting a holistic view of the young Marx and his time that also speaks movingly to the problems of our time.

That success seems to be rooted in two elements:

First, In addition to being very knowledgeable about Marx’s work and time period, Raoul Peck and Pascal Bonitzer, the screenplay writers have largely drawn on the correspondence of the main characters, Marx, Friedrich Engels, his closest colleague and collaborator, and Jenny von Westphalen, his comrade/wife. In doing so, they have allowed us to hear these characters think.

Secondly, Peck’s own life-experience has made him a creative intellectual/filmmaker/political activist, sensitive to the issue of human suffering and emancipation. Born in Haiti, under Duvalier’s dictatorship, he went to the Congo with his family in 1961 where the first democratically elected government of Prime Minister Patrice Lumumba had just been overthrown by U.S.-backed forces loyal to the dictator Mobuto Sese Seko. After living under the dictatorship of Mobutu for many years, he continued his education in France and Germany where he received degrees in industrial engineering, economics, and film. He has had jobs as varied as being a taxi driver in New York, a journalist and later, Haiti’s minister of culture in 1996-1997. During the past 36 years, Peck has made 21 films, most notably, Lumumba, about the Congolese revolutionary and independence leader, and I Am Not Your Negro about the African American writer, James Baldwin. It is this knowledge and life experience that has been brought to bear on his presentation of the young Marx.

The film thus starts with a chilling scene in which poor peasants– women, men and children –collecting deadwood in Prussia’s Mosel forest in the Rhineland, are assaulted, beaten and killed by agents of landowners who arrive on horsebacks. In the background, we hear excerpts from one of Marx’s 1842 essays on the Prussian law on the theft of wood, which he wrote for the newspaper Rheinische Zeitung, where he challenged the very hypocrisy and inhumanity of this law and its use to kill peasants. Film viewers are then taken to the office of the Rheinische Zeitung where the 24-year old editor, Marx (not yet a communist) is challenging his colleagues to be more radical, even as the Prussian police is banging on the door with an order to shut down the newspaper and arrest them.

Peck then, introduces us to Friedrich Engels, the son/employee of a German textile factory owner in Manchester and a socialist intellectual seeking the collaboration of workers to help him write a book about the condition of the working class in England. Marx and Engels meet for the second time at the office of the German philosopher and political writer, Arnold Ruge. They discuss their respective works, ideals and goals, and the rest is history.

Since it is not possible to discuss all the dimensions of Peck’s film, in this short review, I would like to limit myself to three aspects which stand out as unique: I. Marx’s concept of organization; II. Marx’s challenge to the French Anarchist thinker, Pierre Proudhon; III. The role of women.

I. Marx’s Concept of Organization

While a two-hour film cannot possibly allow any writer/director to do justice to the philosophical, economic, political and social issues that Marx was writing about, or Engels and Marx were jointly writing about, what comes through in Peck’s film is the following: Marx saw himself as a philosopher, the originator of a unique critique of political economy and a totally new concept of human liberation. He was not simply exposing income inequality but challenging alienated labor and the alienation of humanity. He was a profound philosopher and economist but also not an ivory-tower intellectual. Thus, he and Engels actively reached out to workers, men and women, to poor people, to other revolutionary intellectuals, and helped transform the League of the Just from an organization that limited itself to “the brotherhood of men” to one whose manifesto became the Communist Manifesto, written and published on the eve of the 1848 Revolutions that shook up Europe.

The fact that Marx’s concept of human emancipation and his views on organization were completely distorted and turned into totalitarian state capitalist societies, as seen in the USSR and Maoist China, does not permit the abandonment of that concept and its relevance for today.

II. Marx’s Challenge to Proudhon

Peck emphasizes how much the development of Marx’s ideas was a response to what he and Engels thought were the inadequacies of Pierre Proudhon’s views. At the same time, we see that Marx and Engels made an effort to reach out to Proudhon in their organizational work, because they respected him as a worker-intellectual and a working-class leader.

The gist of Marx’s critique of Proudhon is expressed in a few scenes in which Marx challenges Proudhon’s view of “property as theft” for being inadequate in its understanding of capitalism and capitalist relations of production, namely alienated mechanical labor and its consequences. Peck also depicts how Marx took it upon himself to do a serious study of Proudhon’s Philosophy of Poverty (1846), and was compelled to write Poverty of Philosophy(1847), as a response.

In his Philosophy of Poverty, Proudhon had argued that if money were abolished and if workers were paid vouchers based on their labor time, the vouchers would allow autonomous cooperatives and communities to have transparent exchange and social relations without the need for a central plan.

Marx, in his Poverty of Philosophy, and later in the Grundrisse, critiqued Proudhon’s thesis and argued that under capitalism too, workers’ wages are based on their labor time. However, the labor time used as the measure of remuneration under capitalism is not the worker’s actual labor time but the minimum labor time for the production of an exchange value. Later in Capital he called this measure, an average or “socially necessary labor time.” He thought that any conception that fell short of comprehending the capitalist mode of production and its fragmentation of the human being, would not be able to offer an alternative that could truly transcend capitalism.

While the detailed content of these books could not be discussed in The Young Marx, the film does show that Poverty of Philosophy was meant as a book for workers as much as for intellectuals. In one scene, Mary Burns, a worker, is shown holding it up at a labor meeting and calling on the participants to read Marx’s response to Proudhon.

III. The Role of Women

Peck makes a special effort to highlight the role and characters of Marx’s wife, Jenny von Westphalen and Engels’s companion, Mary Burns. Jenny von Westphalen was the daughter of an aristocratic family in Trier and had been Marx’s friend from a young age. She was not simply Marx’s wife. As a highly educated woman who had also become a revolutionary, she was a thinker and a comrade who could carry on debates with Marx and assisted him in the development of his ideas. She was independent-minded and articulate. She endured poverty and endless hardships because of having married a revolutionary who kept getting expelled from one country after another for his ideas and activities. However, she did not return to Prussia to live with her aristocratic family, because she truly believed in the cause for which she and Marx were both fighting. All of these dimensions of Jenny Marx come through in the film and make viewers truly admire her.

Mary Burns was also not simply Engels’s companion. She was a militant and vocal Irish worker who challenged the horrible conditions of factory labor and helped introduce Engels to the League of the Just, an organization of revolutionary artisans and workers led by German emigrant artisans, Karl Schapper and Wilhelm Weitling. She was also very interested in the ideas that Marx and Engels were developing, and participated in activities with them to introduce these ideas to other workers.

The last scene in the film in which Marx, Engels, Jenny von Westphalen and Mary Burns are sitting around a table and editing the handwritten copy of the Communist Manifesto, is truly memorable.

IV. Marx’s Relevance for Today

It is the Communist Manifesto, the culmination of the film, that Peck argues, speaks volumes to today’s crisis-ridden capitalism. In an interview about the film, he states: “Both projects [I Am Not Your Negro and The Young Karl Marx] were a sort of response to the world I see around me, and not only here in this country [U.S.] but in Europe and in the Third World. It’s what I call the rise of ignorance, of confusion . . . I just wanted to give a response and come back to what I call the fundamentals.” (https://www.npr.org/2018/02/25/588673944/the-young-karl-marx-looks-inside-the-mind-of-a-revolutionary) In another interview, he states: “Marx was not dogmatic. Marx always said you need to reanalyze your current situation and your historic situation.” (http://www.newsweek.com/young-karl-marx-movie-raoul-peck-director-review-communist-manifesto-communism-818987)

It is not only Marx’s critique of capitalism but also his ability to comprehend reality in a holistic way, to analyze, to be a critical and independent thinker, that Peck thinks we can learn from in order to challenge the growing populism, dogmatism and authoritarianism that is engulfing the world. Peck wants a new generation to know that they can change the world for the better and revolutionize it, provided they begin with the thinkers who give us the foundation to do so.

Hopefully, Peck will go on to make parts II and III of this film to cover the other periods of Marx’s life.

Frieda Afary

March 23, 2018

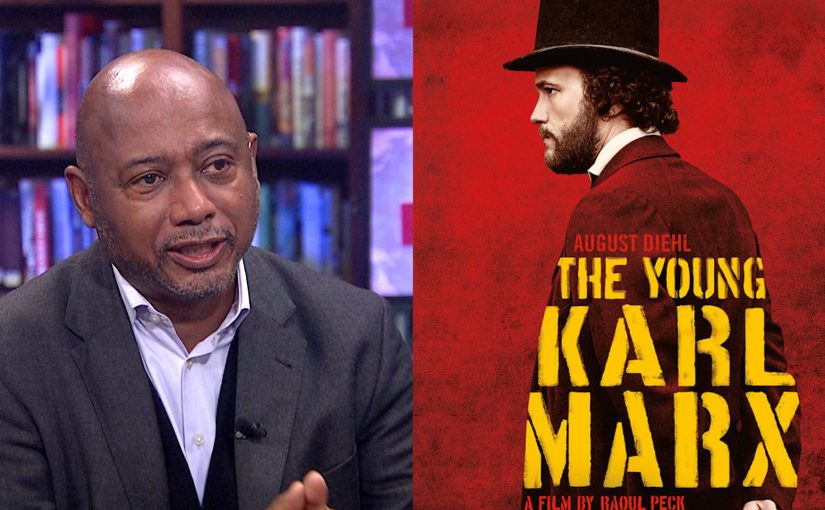

Cast: August Diehl as Karl Marx, Stefan Konarske as Friedrich Engels, Vicky Krieps as Jenny von Westphalen, Hannah Steele as Mary Burns, Olivier Gourmet as Pierre Proudhon, Rolf Kanies as Moses Hess, Niels-Bruno Schmidt as Karl Grun, Alexander Scheer as Wilhelm Weitling.

Director: Raoul Peck

Writers: Pascal Bonitzer and Raoul Peck

Cinematographer: Kolja Brandt

Editor: Frederique Broos

Composer: Alexei Aigui

Languages: German, French, English with English subtitles

Length: 118 minutes

Watch the film online free of charge. Click on the link below.

http://moviesin.co/watch/QvMynJv2-the-young-karl-marx.html#.WutxYUs4gdI.facebook